By Mohani Niza (first published May 11, 2021)

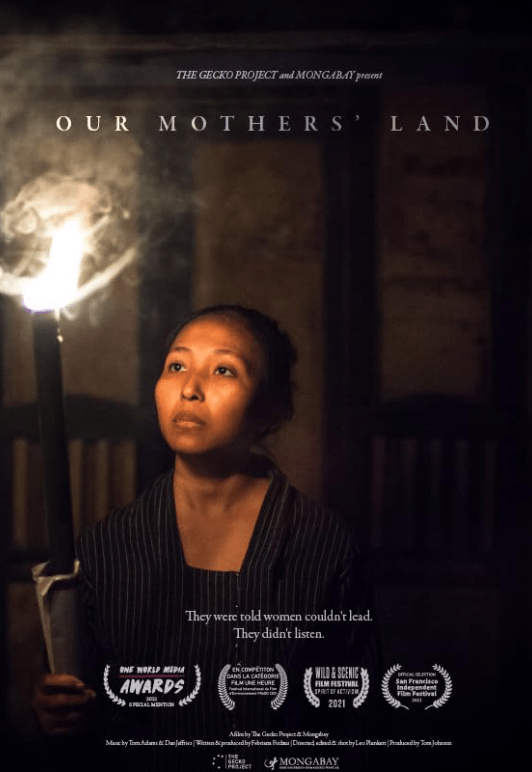

‘Our Mothers’ Land’, a documentary film produced by Mongabay and The Gecko Project, offers an intimate glimpse into the fight by female Indonesian activists against land theft and the destruction of Mother Earth.

Set against the lush greeneries of rural Indonesia, the 55-minute documentary by journalist Febriana Firdaus focuses on these women in groups, and also as individual activists.

One part of the documentary struck me as particularly powerful, and it is during the beginning: a group of women farmers, calling themselves the ‘Kartinis of Kendeng’, were protesting outside the presidential palace in Jakarta, with their feet set in cement. They had arrived here from the mountains of East Java thousands of kilometres away.

Their demand? That a company stops constructing a cement factory on their lands. The media, the public, and police personnel, look with wonder, respect and admiration.

Kartini’s legacy

The name ‘Kartini’, of course, refers to Raden Adjeng Kartini, the Javanese aristocrat who lived under Dutch rule and pushed for the education of women and girls.

More than a hundred years after her death, her legacy lives on. Coincidentally, it was just a week after Indonesia celebrated Kartini Day that I had the opportunity to interview Febriana.

Febriana told me that it was not a surprise that Kartini’s spirit rippled through the generation of Indonesian women till today.

Febriana wrote, produced and narrated the documentary while Leo Plunkett directed it. Febriana is an investigative journalist who mainly reports stories about eastern Indonesia, covering issues such as corruption, anti-LGBTQ discrimination, and West Papuan independence. She has written for publications such as Al Jazeera English and the Guardian.

‘Our Mothers’ Land’ is her first foray into film.

“I feel so inspired by women from indigenous communities because they are very strong,” Febriana told me over an interview via Zoom from her house in Indonesia.

The participation of Indonesian women in activism has been particularly thriving, according to numerous research.

Women in this Southeast Asian nation involve themselves in national debates in areas such as Gender-Based Violence (GBV), economic inequality and child marriage, despite strong pushbacks by corporations and religious quarters.

Despite this, Febriana explained that many Indonesians still feel that women should belong in the home. “In Javanese society for example, there are jokes about how a woman should belong to the kitchen, a woman should not do this or that, and not get higher education because they will end up in the kitchen.”

Emotional toll

Filming the women was no easy task at first as Febriana faced some initial hesitance among the women.

“They thought it’s okay, we organised but the men will be speaking to the media,” Febriana said. “I had to make them trust me that it is okay and have their own voice to talk about this movement. I think what made it easy was because I’m a woman so it’s easier for me to approach them.”

The women relayed many harrowing tales; not all featured in the final cut.

Febriana took long hours to interview the women, which posed an emotional toll on her.

An example was when she interviewed Daria, a young farmer who was heavily pregnant when her husband was taken away by the police. While joining a protest to demand for his release, Daria got into an accident, and was left with no money to pay her hospital bills.

During the interviews, Febriana would often hold hands with the women, with Febriana choking back tears.

“I’m trying to be strong but actually I wanted to cry,” she said. “Whoever these women are, and from whichever part of Indonesia they come from, they all have had to pay a price for speaking up.”

If the women were hesitant at first to speak, the men, on the other hand, were eager to participate. Febriana and Leo had to say no to the men, which upset them.

“There was so much I couldn’t explain to them, like the concept of privilege and access and how women usually don’t get to talk,” Febriana said.

Febriana and Leo believe that placing women at the forefront – especially in the case of the ‘Kartini Kendeng’ protest – proved to be a good strategy by land rights activists.

The authorities were a bit more sympathetic and willing to negotiate with the women – in fact, the women from the ‘Kartinis of Kendeng’ protest managed to secure an audience with President Jokowi.

“With the women, the authorities have this emotional barrier, like a social barrier,” Febriana said, explaining that this was perhaps because authorities felt connected to the women whom they liken to their mothers, sisters and daughters.

Febriana said she approached the women’s rights angle for this documentary because of the lack of media coverage on the topic.

“If you notice, after the Black Lives movement, there is a new discussion about this intersection between environmental issues and women’s issues,” she said. “We need to understand that the most affected and vulnerable communities are women and children.”

Though Febriana insists that environmental rights should not be confined to just a women’s issue, she said that the proximity and the relationship between women and the earth make it a worthwhile topic.

“Everyone should have sensitivity about the issue of nature, about land.”

———————————————————————————-

‘Our Mother’s Land’ has received much international praise. In January 2021, it was screened at the 19th Wild & Scenic Film Festival where it received the Spirit of Activism Award.

It was also an official selection of the San Francisco Independent Film Liveable Planet event 2021.

The documentary has also made into the long-list of One World Media Award 2021, competing with big names such as the Guardian, BBC, and Thomson Reuters Foundation.

You can watch the documentary here.

Leave a comment